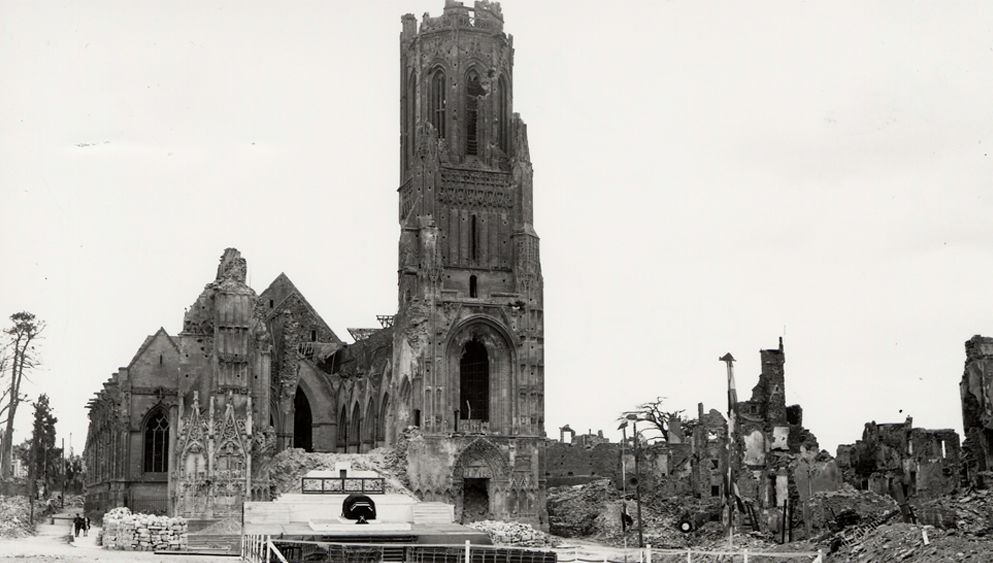

1) THE BOMBING OF SAINT-LÔ, June 6-7, 1944.

Text by Mr. Michael Yannaghas – Saint-Lô 44-Roanoke Association

General Bernard Law Montgomery, in overall command of Allied land forces on D-Day, wanted to prevent the Germans from reinforcing the beachhead fronts by bombing 9 major Norman rail and road cenlres, including Caen, Saint-Lô, Argentan, Coutances, and Vire.

The first raid on Saint-Lô had been planned for 09.00 June 6, 1944, by U.S. 8th Air Force bombers. However, on arriving over target the cloud was so thick that the mission was aborted and rescheduled for 20.00.

The evening of June 6, 1944 was cloudless, and when a force of some 30 bombers arrived over Saint-Lô, the majority of the town’s 11,7OO inhabitants were at home. The first raid lasted approximately between 19.55 and 20.10, and once the planes had gone, many inhabitants left the town to find shelter in the surrounding countryside.

The second raid, which took place between 00.50 and 00.58 during the night of June 7, 1944, was by the R.A.F., attacking with 104 bombers. Some 2,100 high explosive 500 pound/250 kilo. bombs were dropped on the town, 10% of which were delayed action.

Between 300-400 inhabitants were killed.

During these 2 raids, which, together with further raids in June, destroyed around 90% of the town: Samuel Beckett’s “Capital of the Ruins”.

There were 2 warnings for the bombings: the first was by leaflet on June 5 dropped from U.S. “Flying Fortresses”. Unfortunately, these were blown away by the wind to land in fields some 5 miles/8km. away. A few did land in the town but, according to a witness, being completely anonymous, they were not considered to refer to Saint-Lô. The second warning came from the B.B.C. at 13.30 on June 6 telling people in towns 30 miles/ 55km. from the coast to leave immediately, especially from those towns on which leaflets had been dropped… Unfortunately, the Germans had already confiscated radio sets in April…

2) THE BATTLE OF SAINT-LÔ.

Text by Mr. Michael Yannaghas – Saint-Lô 44-Roanoke Association

The principal forces attacking Saint-Lô comprised :

• Major General Gerhardt’s 29th lnfantry Division to the North-East.

• Major General Baade’s 35th lnfantry Division to the North-West. Both part of Major General Corlett’s 19th Army Corps.

The German units defending Saint-Lô were commanded by Parachute General Eugen Meindl and included :

• The 3rd Parachute Division of Lieutenant General Schimpf, east of the lsigny Road, defending Martinville Ridge and beyond.

• The 352nd lnfantry Division, of Lieutenant General Kraiss, west of the Paratroopers, in and north of thetown. Attached tothis Division were 3 Battle Groups from other infantry divisions.

The 29th Division resumed the offensive for the final attack on the town on July 11, 1944 and the capture of Hill 192, one of the key German defensive positions North-East of the town, by the 2nd lnfantry Division, the following day, allowed the 29th Division to attack along Martinville Ridge.

To the right, the newly-arrived 35th Division went into action for the first time, pushing southwards towards the River Vire.

Stubborn German resistance greatly slowed both Divisions’ progress, however on July 15, 1944, the 116th’s 2nd Battalion, having not received the order to stop and dig in, managed to break through the German lines at Martinville itself and advanced right up to the La Madeleine crossroads on the Bayeux Road. lt was however totally isolated.

July 16, 1944 : Major Tom Howie – appointed 3 days earlier in command of the 116th’s 3rd Battalion – was ordered to link up with 2nd Battalion’s isolated men and then advance westwards together along the Bayeux Road into Saint-Lô. The same day, Gerhardt, created Task Force C under the command of his Assistant Divisional Commander, Brigadier General Cota. This was a mobile force of about 600 men in tanks, tank destroyers and armoured cars which assembled

at Couvains.

July 17, 1944 : Howie, taking advantage of early morning mist, silently led the 420 men of his battalion through the German lines down Martinville Hill and up to the 2nd Battalion. But he found these men completely exhausted and incapable of further action.

He so informed his Regimental Commander, Colonel Dwyer, who asked Howie whether his 3rd Battalion could carry out the attack alone. Howie replied “Will do”, the phone conversation ending with the words “See you in Saint-Lô”. He

then issued his orders to his officers, again ending “See you in Saint-Lô” but just as they were dispersing to attack, around 07.45 the Germans directed a mortar barrage at the crossroads and Howie was mortally wounded in the back by a piece of shrapnel.

With these two battalions now blocked in the East, Gerhardt changed his original plan to assault the town from the West. He thus ordered the 115th Regiment to advance to the north-western outskirts of Saint-Lô.

Meanwhile, General Meindl was faced with an impossible situation. After very heavy losses and the unavailability of reinforcements or any reserves ; he was sure his troops could well be encircled. All his requests for reinforcements or the authortsation to withdraw so far had been denied. The fact that Field Marshal Rommel in driving to visit the Saint-Lô front was badly injured after his car was strafed that day did not help matters.

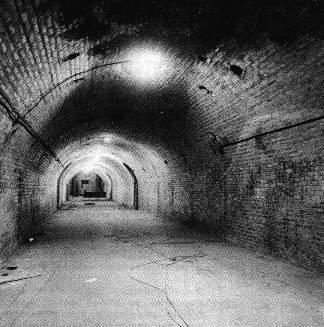

3) THE BUNKER IN THE ROCK..

Text by Mr. Michael Yannaghas – Saint-Lô 44-Roanoke Association

The Germans began working on this project in March 1943. The work was carried out by a German civilian firm who had an office with a staff of 3, in the Place des Beaux-Regards above. The workforce consisted of 5 German civilians (1 engineer, 2 supervisors, l” mechanic and 1 driller), 10 Frenchmen requisitioned under the Service de Travail Obligatoire or « Obligatory Labour Service », 4 North Africans and 2 ltalian bricklayers.

They advanced by drilling about 15 holes some l.5 meter long at a time, which were filled with sticks of dynamite. Before lighting the fuze, a trumpet was sounded at the entrance to notify the nursing staff in the town’s hospital on the other side of the road to open all the street-side windows.

After the explosion, the workforce started clearing away all the cubic meters of schist rock and gravel using the narrow-guage Decauville railway system with 60 cm.-wide rails, as in First World War trenches and quarries. The hardcore was loaded into a fleet of requisitioned lorries and dispersed around the countryside.

It has been estimated that some 3,250 cubic metres or 8,700 tons of rock was extracted to create the galleries visible today.

Rubber sheeting was affixed to the ceilings with hot tar and cemented over, and the walls were also cemented before the bricklayers added the final touch.

Lighting was provided by a petrol-driven electrical generator.

We are still unsure why the Germans dug these galleries. Was it for a military hospital ? Or a command post ? Or an ammunition depot ? lt is thought that the latter is the most likely reason, as a hospital does not need the armoured doors seen in the corridor, and there were already civilian and military command posts in the town.

June 6, 1944 : after a night of intense aerial activity, the maternity section of the hospital was evacuated together with the elderly patients, leaving some 60 people in all, including 17 nuns who were part of the nursing staff. Sister Lucie, the Mother Superior, being worried for the safety of the remaining patients and staff, went to see the German officer in charge, to obtain permission to evacuate them to the bunker. (ln 1944 the hospital was divided in two – one part for wounded German soldiers, the other for civilians). Whereas he was initially unwilling to grant the necessary authorisation, he gave in to her persistence, and by the end of the afternoon, all remaining patients and staff had moved to the galleries.

After the first bombardment of 8.00pm, and long into the night, many hundreds of the town’s inhabitants found refuge here, including children, the elderly, the sick, wounded civilians and German soldiers, as well as some American parachutist prisoners.

June 7, 1944 : Luckily, there was a doctor, a surgeon and a pharmacist amongst the refugees, but there was no anaesthetic for any necessary surgical operations. The nuns were able to collect as much useful equipment as possible from the hospital ruins, including bandages, disinfectant, candles and bed-pans and chamber pots, there being no WC.’s in the galleries.

There was neither any drinking water available for the refugees, the water from the galleries’ well not being potable. However, the farmer who used to deliver milk to the hospital continued to do so leaving his churns at the entrance. Some cider was also found in the hospital cellars. 700 portions of bread were distributed in the morning, from a supply found in an abandoned bakery by the Vire Bridge.

June 8, 1944 : during the morning, after the petrol for the generator had run out, the Germans started talking to those refugees in good physical condition about leaving the galleries, to which about one third agreed.

June 9, 1944 : in the morning, the Germans ordered everyone to leave and the galleries were cleared by the end of the afternoon. We don’t really know whether the Germans used the bunker after June 9, or the Americans after the town was liberated on July L8.

After the war : the galleries became a storage area – by the town’s Civil Engineering Department, by the police for Lost and Found items, by a Wines and Spirits merchant. Towards the end of the 1950’s, the Elle & Vire dairy cooperative took advantage of the galleries’ constant 14 degree C. (about 60 degree Fahrenheit) temperature over some 10 years to mature their cheeses.

ln 1970, the galleries were used for the first time as a museum over several months with a display of wartime photos. However the original idea for a permanent town museum was abandoned in view of the high cost of making the galleries safe for receiving the public.

Between May and September 1994, during the D-Day commemorations, a larger second display of wartime photos was installed in the galleries and seen by some 10,000 people.

Today : internally, the Bunker is exactly how it was in June 1944 apart from the lighting and paintwork. Externally, the entrance is some 2 meter below the road level which was raised to protect the lower town from possible flooding of the Vire, using rubble from the bombed buildings. The large grill on the cliffside to the left of the door is the mouth of the air vent for the galleries.